The Medieval Altarpiece in Grace Cathedral, San Francisco

A study (with photos) published in 2005 in the

Galerie Nef.

This Flemish medieval altarpiece dates from the beginning of the 16th century.

It belonged to the Hambye Abbey, Normandy, for three centuries, until the French

Revolution (1789). After being sold, it changed owners several times, before

finishing its trip at Grace Cathedral, San Francisco, California, in 1930. The

two short texts about Hambye Abbey and

Grace Cathedral are intended to place the story of the

altarpiece in context. They are followed by an in-depth

article about the altarpiece itself, and a series of

photos by Tim Aldridge. This study is also available in

French.

This Flemish medieval altarpiece dates from the beginning of the 16th century.

It belonged to the Hambye Abbey, Normandy, for three centuries, until the French

Revolution (1789). After being sold, it changed owners several times, before

finishing its trip at Grace Cathedral, San Francisco, California, in 1930. The

two short texts about Hambye Abbey and

Grace Cathedral are intended to place the story of the

altarpiece in context. They are followed by an in-depth

article about the altarpiece itself, and a series of

photos by Tim Aldridge. This study is also available in

French.

|

A Few Words on Grace Cathedral, San Francisco (California)

A Few Words on Hambye Abbey, Normandy

An Altarpiece of Hambye Abbey at Grace Cathedral, San Francisco

A Series of Photos of the Altarpiece

The French Version

By Marie Lebert. Translated by Michael Lampen, Archivist of Grace

Cathedral.

The city of San Francisco was really born in 1849, at the start of the Gold

Rush. A first Grace Chapel (Episcopal) was built at that time. A larger church

of 1851 was replaced in turn by a neo-Gothic brick church in 1860. That church

was destroyed in the great fire that followed the 1906 earthquake. Also

destroyed was the Crocker property on Nob Hill, the late senior Crocker having

made a fortune in railroads. Three quarters of the city were also destroyed. The

Crocker family donated their city block to the Diocese of California for the

construction of a cathedral. They also gave several liturgical art objects,

including the medieval Hambye retable. The architect, Lewis P. Hobart, designed

the final cathedral plan in 1928. Construction was completed in 1964.

Inspired by French and Catalan Gothic cathedrals,

Grace Cathedral is one of eighty-one

Episcopal cathedrals in the United States, the third in stature after those in

New York and Washington D.C. Built of steel and concrete to resist earthquakes,

the cathedral is very imposing, with a length of 329 feet (100 meters), a nave

rising 89 feet (27 meters), façade towers 174 feet (53 meters) tall and a fleche

reaching 247 feet (75 meters) above ground. The cathedral and its attendant

buildings and grounds cover 2.6 acres (1 hectare).

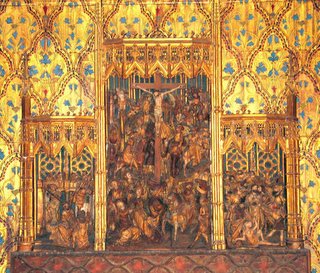

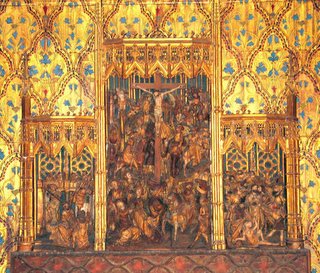

The retable of Hambye Abbey is situated in the Chapel of Grace, completed in

1930 as the first unit of the future cathedral. Situated on the site of the

front steps of the William H. Crocker mansion, this chapel was inspired by the

Sainte Chapelle, Gothic jewel built by Saint Louis on the Ile de la Cité in

Paris. Mrs. Crocker donated the retable. The mural behind the retable (1931) was

inspired by decorations on the columns of the shrine platform in the Sainte

Chapelle. The retable sits on a medieval French

limestone

altar, dating from 1430. The history of the altar is being researched.

By Marie Lebert. Translated by the author.

Located in the Norman countryside, not far from Mont Saint-Michel, Hambye

Abbey was founded around 1145 by Guillaume Painel, Lord of Hambye, and by

Algare, Bishop of the Diocese of Coutances. The monastery was established by a

group of Benedictines from Tiron (in the Perche region, southern Normandy).

Lead by an ideal of strictness and austerity similar to the Cistercian ideal,

these Benedictines built the abbey at the end of the 12th / beginning of the

13th century, with the typical sober and elegant design of the early Gothic

period. The religious community reached its climax in the 13th century. After a

long decline over the following centuries, it disappeared in the 1780s.

Like all the French abbeys of the time, Hambye Abbey was declared National

Property in 1789, at the beginning of the Revolution (1789-1799). It was sold in

1790. The owners transformed or destroyed the buildings, and broke up the

furniture. The altarpiece was sold away, after having been owned by the abbey

for three centuries (16th-18th). The conventual buildings became farm buildings.

The abbey church began use as a quarry in 1810, and was partly dismantled over

the years.

Hambye Abbey was put on the French Historical Register in 1905. It has one

of the most complete conventual buildings in the region, despite the loss of the

refectory and most of the cloister. The imposing ruins of the church dominate

the conventual buildings, which are composed of a sacristy, a beautiful chapter

house with two naves and a polygonal apse, a scriptorium, a kitchen, a cider

press, a stable and a cowshed. The restoration of the abbey began in 1960 under

the direction of Elisabeth Beck, the owner of the abbey with the Departmental

Council of Manche. The various buildings now house antique furniture, tapestries,

large painted canvases (the well-known colorful "toiles peintes" of Hambye),

religious ornaments and liturgical objects. The abbey is open to the public part

of the year, between Easter and the end of October. It houses exhibitions,

concerts and symposiums.

By Bernard Beck, Secretary of the Association des amis de l'abbaye

d'Hambye (Association of Friends of Hambye Abbey). Translated by Michael

Lampen, Archivist of Grace Cathedral.

In the spring of 2002, Marcel Briard, teacher of German at the Leverrier

School of Saint-Lô, and who has for a long time been tour guide of the abbey,

found, on the internet site of

Grace Cathedral, San Francisco, an original and important discovery which

enriches considerably the story of the heritage of our abbey (and at the same

time demonstrates the capacity of this new medium for information research). The

Grace site in effect allows one to virtually visit this Californian neo-gothic

cathedral and to make note of its riches for which well-documented notes give a

description.

However, among the art works conserved in the cathedral is a Flemish Gothic

altarpiece with the provenance of Hambye Abbey.

We have now made contact with the archivist of the cathedral, Michael Lampen,

by the mediation of our friend Marie F. Lebert, who has made many trips to

California. Michael Lampen has very kindly sent us the study of Lynn F. Jacobs,

published in 1997 in the Jaarboek van Het Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten

Antwerpen (Annals of the Royal Fine Arts Museum of Antwerp) under the title:

A Netherlandish Carved Altarpiece in San Francisco’s Grace Cathedral.

The Flemish borderlands, Flanders (Brussels and Antwerp) were in the 15th and

16th centuries a major region for the production of carved wooden altarpieces,

destined mostly for export, and of which about 350 survive today, mostly in

Europe. The United States, by the means of collectors' purchases and museum

donations, has five, including that of San Francisco. The Walters Art Gallery in

Baltimore has an altarpiece of the Passion (Brussels, end 15th century) with the

provenance of the collegiate church of Blainville-sur-Crevon, near Rouen, which

is not without interest as explained below.

The Grace altarpiece, executed at the very beginning of the 16th century, is

made of three panels (triptych): in the center the Crucifixion, at left the

Crowning with Thorns, at right the Kiss of Judas and the Arrest of Jesus.

However, the "frame" and its Gothic architecture are a modern reconstruction,

which leads Lynn F. Jacobs to assume that the altarpiece normally had two other

scenes (lost) and had been composed - in the usual scheme of Flemish altarpieces

- of three panels of equal dimension: in the center the Crucifixion, at left the

superposed scenes of the Arrest and the Crown of Thorns, at right two episodes

after the Crucifixion.

In any case, despite the modifications, this altarpiece possesses an

incontestable interest and can be compared to numerous identical conserved works

in churches and museums.

But how did it get from Normandy to California?

That a Flemish altarpiece existed in Hambye Abbey is not surprising. The

trade in such works was known at the end of the 15th century and in the 16th.

They were easily transported by boat from Antwerp to Rouen or to a coastal

Normandy port. The region still has the altarpiece of the Nativity in Rouen

Cathedral (today in the Antiquities Museum of Seine-Maritime) and the altarpiece

of the Passion in the church at Vétheuil, to which one could add that of

Blainville-sur-Crevon (today in the United States). Coutances Cathedral also

sheltered in a side chapel of the nave (Saint Francis Chapel), a wooden panel

sculpted at the beginning of the 16th century (the Arrest of Jesus) which has

every likelihood of also being a Flemish altarpiece.

One was able to retrace the travels of our altarpiece to the United States

beginning in 1890. On that date a French collector, the Marquis of Fressange,

bought it from a farmer, a neighbor of Hambye Abbey. His grandfather has

acquired the work during the Revolution, at the sale of the abbey furniture (3rd

Prairial, year two of the Republic, or May 23, 1794). And in fact, the inventory

of the furniture drawn up for the national sale of the abbey goods makes

reference to "the abbey altar with its altarpiece". The buyer was named

Levillain, of Hambye, and he also acquired three other altars, two buffet

tables, a lectern, statues, a painting and diverse pieces of furniture among

which were "an armoire with three panels, enclosing the papers of the charter of

Christ" (Niobey, Hambye, le château, l'abbaye (Hambye, the Castle, the

Abbey), Saint-Lô, imprimerie (printing house) Jacqueline, 1940). The altarpiece

and its retable were bought for 60 livres and the armoire for 42. The altarpiece

might be our Flemish altarpiece, at least if the armoire "with three panels"

hadn't already reused the panels. The Marquis of Fressange sold the retable to

the Louvre Museum by dealing with the conservator, Molinié. He sold it to a

Parisian art merchant, Raoul Heilbronner, who gave it then to his son-in-law,

the merchant Maurice Stora. He traded the altarpiece in 1931 to Mrs. William H.

Crocker of San Francisco who gave it to Grace Cathedral (cathedral

archives).

Nevertheless, the circumstances in which Hambye Abbey acquired the altarpiece

are still obscure. Lynn F. Jacobs thinks, with reason, that the monks were not

averse to enriching their church in the decades and centuries (17th-18th) which

followed. Two reasons may corroborate this theory: the slow decline of the

monastery in the modern period and the progressive decline of the community and

its resources. And then there is the evolution of taste. It is difficult to

imagine that a reformed abbot like Jean de Ravalet in the last third of the 16th

century, or Alphonse-Louis de Richelieu in the middle of the 17th century, had

offered to their abbey an "antique" in the true sense of that term. The

altarpiece was thus certainly given to the abbey at the beginning of the 16th

century.

This seems logical enough, but who bought the work or offered it to the monks

of Hambye? The reconstruction of our abbey's history is, as one knows, made

difficult by the loss of archives (due to the fact of the mediocre upkeep of the

charter by the last monks, the dispersal of papers during the French Revolution,

and the bombing of Saint-Lô and the burning of the Departmental Archives of

Manche in 1944). Also it was necessary to patiently reassemble the elements from

other sources. In 2001, we signaled the existence in the Renaissance of two

Hambye abbots forgotten by history, the Italian Hippolyte Bellarmato (1549-1555)

and Louis d'Estouteville, called the Protonotaire (1504-1512), second son of

Jacques d'Estouteville and of Louise d'Albret and grand-nephew of Cardinal

Guillaume d'Estouteville.

This grand d'Estouteville family is narrowly tied to our abbey by the

marriage in 1415 of Jeanne Painel and Louis d'Estouteville. From the second half

of the 15th century she gave proof of her taste for art and her patronage, as

showed in the building work of Cardinal Guillaume (in Rouen, in Gaillon, in Mont

Saint-Michel, in Rome) and in the donations of Jacques d'Estouteville and Louise

d'Albret to the Abbey of Valmont (tombs of the Six-Hour Chapel). Young Louis,

their son, born in 1484, became, thanks to the support of his family, Abbot of

Valmont when he was 10 years old. Ten years later (1504), he became Abbot of

Hambye over Béraut de Boucé, who was the candidate of the monks. In 1514 he

became Abbot of Savigny. In 1520 two canons proposed - without success - his

candidature as Bishop of Coutances. He was also, from 1501, canon of Rouen

cathedral, and became much later, in 1512, dean of the cathedral chapter. In the

same year he left his office as Abbot of Hambye in favor of Béraut de Boucé, and

did the same at Valmont in 1517 in favor of Jean Ribaut, thus conserving only

his abbacy at Savigny and his canoncy at Rouen.

However, Louis d'Estouteville showed himself in each of his ecclesiastical, a

delicate patron, in keeping with family tradition. At Valmont he gave a window

for the abbey choir. He paid for his admission to the Rouen Cathedral chapter

with a statue of Our Lady, destined for the Saint Romain portal, paying 37

livres to the "imager" Pierre des Aubeaux (sculptor with Rolland Leroux, of the

tomb of the cardinals of Amboise in the cathedral). His Hambye abbacy was

obtained against the assent of the monks and by an act of the Parliament of

Rouen, so it is not impossible that Louis d'Estouteville had wanted to placate

the community by offering a beautiful Flemish altarpiece.

But a last point still merits attention and may confirm this theory. We have

mentioned earlier the altarpiece of the collegiate church of

Blainville-sur-Crevon (at the Walters Art Gallery). It is noted that the

Estouteville-Torcys, a cadet branch of this powerful family, were lords of this

parish and that at the end of the 15th century, their representative was Jean

d'Estouteville-Torcy, grand master of arbaletiers, knight of the Order of Saint

Michel. It was he who, in 1490, founded with his wife, Françoise de la

Rochefoucauld, this grand collegiate church of Blainville. The dedication was

made on Saint Michael's day, 1492, by the Archbishop of Rouen, Robert de

Croixmare.

That the Collegiate Church of Blainville and Hambye Abbey both possessed a

Flemish altarpiece, and that both were dependent at the time on d'Estouteville,

doesn't constitute as much of a proof of the intervention of this grand family

(it would be necessary to recover the receipts of the altarpieces), but is at

least a strong presumption. One can reasonably think that is was this young

prelate, the protonotaire Louis, who was the buyer of this beautiful altarpiece,

which, after having spent three centuries as the ornament of our abbey, is today

that of an American cathedral.

[Note: A first version of this article (in French) was published

in the 2003 Bulletin de l'Association des amis d'Hambye (Bulletin of the

Association of Friends of Hambye Abbey).]

Bernard Beck is an historian and writer living in Caen, Normandy. He has

written numerous books, among which are: Quand les Normands bâtissaient les

églises: 15 siècles de vie des hommes, d’histoire et d’architecture religieuse

dans la Manche (When the Normans Were Building Churches: 15 Centuries in the

Life of Men, History and Religious Architecture in Manche) (OCEP, 1981);

Châteaux forts de Normandie (Fortified Castles in Normandy) (Ouest-France,

1986); and: Bernard de Tiron, l’ermite, le moine et le monde (Bernard de

Tiron, the Hermit, the Monk and the World) (Editions de La Mandragore, 1998).

Bernard Beck is also the editor of a monumental book in two volumes:

L’architecture de la Renaissance en Normandie (Renaissance Architecture

in Normandy) (Presses Universitaires de Caen & Editions Charles Corlet, 2003).

Marie Lebert is an independent researcher and journalist. She wrote a study

about Romanesque art in the Bay of Mont Saint-Michel

and another one about medieval architecture in

Jerusalem. She is keenly interested in how digital technology has changed

publishing for books and images. She has written three books on the subject: From the Print Media to the Internet

(NEF, 1999), Le Livre 010101 (The

010101 Book) (NEF, 2003) and Le Dictionnaire du NEF

(The NEF Dictionary) (NEF, 2005). Her favorite places are San Francisco, Paris

and Normandy.

Galerie Nef

NEF: Home Page

© 2005 Bernard Beck (text), Marie Lebert (text & translation), Michael

Lampen (translation), Tim Aldridge (photos). All Rights Reserved.

This Flemish medieval altarpiece dates from the beginning of the 16th century.

It belonged to the Hambye Abbey, Normandy, for three centuries, until the French

Revolution (1789). After being sold, it changed owners several times, before

finishing its trip at Grace Cathedral, San Francisco, California, in 1930. The

two short texts about Hambye Abbey and

Grace Cathedral are intended to place the story of the

altarpiece in context. They are followed by an in-depth

article about the altarpiece itself, and a series of

photos by Tim Aldridge. This study is also available in

French.

This Flemish medieval altarpiece dates from the beginning of the 16th century.

It belonged to the Hambye Abbey, Normandy, for three centuries, until the French

Revolution (1789). After being sold, it changed owners several times, before

finishing its trip at Grace Cathedral, San Francisco, California, in 1930. The

two short texts about Hambye Abbey and

Grace Cathedral are intended to place the story of the

altarpiece in context. They are followed by an in-depth

article about the altarpiece itself, and a series of

photos by Tim Aldridge. This study is also available in

French.